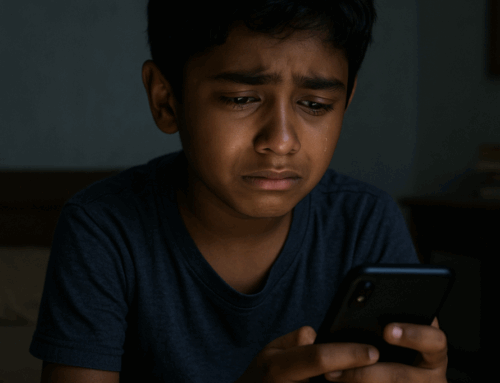

When Sajid received an unexpected call from his daughter’s school it prompted a frantic dash across town. Upon arrival, he was led into a small office where his daughter sat, waiting for him. The school’s safeguarding team gently revealed the cuts on her arm. What began as an innocent online friendship with a “boy” quickly spiralled into a nightmare of manipulation and blackmail. The “kind and attentive” persona was nothing more than a digital mask, concealing the face of a predator who had coerced her into sharing private photos. The man demanded in-person meetings, threatening to expose her most vulnerable moments if she refused. She had been living in the agony of fear, cutting herself to manage the pain and too ashamed to tell her family what had happened.

Sajid’s daughter, like too many others, had fallen victim to the dark side of the digital world – a realm where trust is easily gained and cruelly exploited. This wasn’t just a case of a teen romance gone wrong. This was sextortion – a crime that’s becoming all too common in our hyper-connected world

What is Sextortion?

Sajd’s experience is not unique. “It’s every parent’s worst nightmare. You think you’ve done everything right, taught them about online safety, but these predators…they’re always finding new ways in.”

According to Jacqueline Beauchere, head of safety at Snap, “Online sextortion occurs when an abuser somehow acquires or claims to have intimate imagery of an individual and then threatens or seeks to blackmail the target.” The predator’s ultimate goal? As Beauchere explains, they demand “money, gift cards, more sexual imagery, or other personal information in exchange for not releasing the material to the young person’s family and friends via online channels.”

The phrase “acquires or claims to be in possession” highlights the manipulative nature of sextortion. The abuser may have compromising images, or they might be bluffing – either way, the threat feels all too real to the victim. When Beauchere mentions “threatens or seeks to blackmail,” she’s pointing to the core of sextortion: the exploitation of fear and shame. The abuser uses these emotions as leverage against their target.

Beauchere’s reference to “demanding money, gift cards, more sexual imagery, or other personal information” showcases the varied forms of sextortion. It’s not always about money; sometimes, the goal is to perpetuate the cycle of abuse or gather more sensitive data. Finally, the phrase “in supposed exchange for not releasing the material” is crucial. The key word here is “supposed.” As our opening story illustrates, there’s often no end to the demands once a victim complies.

Sextortion is made possible by sexting

To understand sextortion, you need to understand sexting. Sexting – the act of sending sexually explicit messages or images electronically – has become increasingly normalized in modern dating culture, both for teenagers and adults. What started as private, intimate exchanges between consenting individuals has opened a Pandora’s box of potential exploitation.

Amanda Lenhart, a researcher in digital communication trends, describes sexting as sending “sexually suggestive, nude, or nearly nude photos or videos of yourself” (Lenhart, 2009, p. 16). This definition covers both the sharing of photos and messages.

Lenhart’s research, conducted by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project, provides insightful statistics on sexting among teenagers. In a nationally representative survey of 12-17-year-olds, the study found that 4% of cell phone-owning teens in this age group reported sending sexually suggestive nude or nearly nude images of themselves via text messaging. A larger percentage, 15%, said they had received such images of someone they know.

The research also revealed an age-related trend: older teens were more likely to engage in sexting. Among 17-year-olds with cell phones, 8% reported sending a sexually provocative image by text, while 30% had received a nude or nearly nude image on their phone.

Cultural Differences Over Personal Photographs on Social Media

Jamila, an Iranian mother of two teenagers living in the UK, articulates a common fear in her community: “If someone goes into a relationship with somebody, they might take pictures,” she warns. “They use those pictures and put your daughter in danger, saying, ‘If you’re not with me anymore, I can use it in public, in social media.'”

Growing up in Iran, Jamila’s experience was marked by strict limitations on interactions with the opposite sex. She recalls, “You could never speak with a boy. I couldn’t, because I was scared and worried they might take a picture of me and show it to my family. Then they’re going to kill me – my brother, my father, my mother.”

Jamila’s transition from Iran to the UK represents more than just a geographical move; it’s a leap between two vastly different worlds in terms of social norms and expectations. In her home country, the mere act of speaking to a boy could have severe consequences. Now, in the UK, she faces the challenge of navigating a more open society while still carrying the weight of her cultural upbringing.

For immigrant parents like Jamila, ensuring their children’s online safety takes on an additional layer of complexity. They must balance their traditional values and fears with the realities of digital communication in their new home.

Article written for Power of Zero by Eiman Jamil who holds a MA in Visual Journalism from the University of South Wales and is the author of Imran Khan: A Seasoned Politician.

Leave A Comment