The issue of bullying is complex in its psychological and sociological complexity. In this article Mark Friis Hau shows how anthropology is supporting schools in Denmark in becoming bully-free. This article was first published by our friends at Antropocon

As in most Western countries, bullying among schoolchildren has until now been a big problem in Denmark. Children who suffer from bullying not only experience a lack of well-being during their school days, but can also suffer from increased loneliness, higher degrees of unemployment, and a higher risk of suicide as adults.

In an effort to curb a negative trend, the Danish public school system has for the past decades been using ethnographic methods and anthropological understandings of ‘community’ to better understand why some children bully others and what can be done about it. This qualitative method has had amazingly positive results.

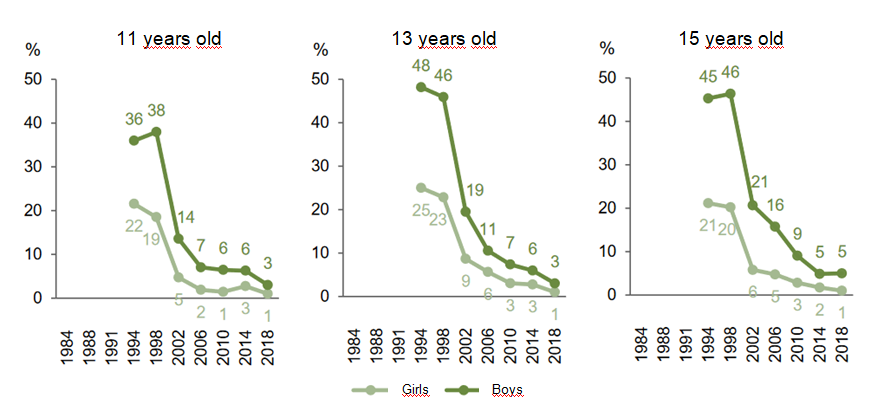

The Danish Skolebørnsundersøgelsen is part of the large, international project, ‘Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) – – a WHO Collaborative Cross-National Survey’, which now extends to 42 countries. Through questionnaires sent out every four years, the survey aims to deliver data on self-reported health and well-being among 11-15 year olds. This year’s survey in Denmark showed a very interesting development: The percentage of children who had bullied others had dropped drastically, from a high point of over 40% in 1998 to less than 5% in 2018.

This drop translates into only one in twenty children experiencing bullying in 2018 compared with one in every three in 1998, and has put Denmark at the top of European countries in terms of success stopping bullying. It is only surpassed by Iceland and Sweden, who have likewise made heavy use of qualitative methods in order to combat bullying among schoolchildren.

«What we’ve been successful at is broadening the term ‘well-being’», says Jannie Moon Lindskov, director of the Danish Center for School Environment (DCUM). «We no longer look at the individual child being bullied or bullying, we look at the class community. I think this has helped drive the positive development» (Folkeskolen.dk).

Researcher Helle Rabøl Hansen, who studies bullying through ethnographic methods, notes how bullying creates a harmful community among those who bully, and lead to feelings of isolation for those who are bullied. In this way, bullying becomes a social survival strategy that creates strong in-group feelings of belonging and harmful effects for those kept out. However, Rabøl Hansen argues that a sense of community is also exactly what can stop bullying, it just needs to be harnessed as a class. «This is where teachers come into the picture. The pupils need to feel that they’re working together on something – social and educational projects need to go hand in hand.»

It is not only concerning methodological expertise that anthropology has something to offer in designing better policies. While qualitative investigations of schools and children’s well-being have been instrumental in reducing bullying, researchers also seem to have adopted more deep-seated anthropological knowledge of the relationality of community and the importance of interpersonal relationships.

When researchers emphasize community, it is no wonder ethnographic methods and anthropology have had much to offer in Denmark’s successful fight against bullying. From Malinowski to Anthony Cohen or Fredrik Barth, anthropologists have long worked with issues of belonging, community, and in-group/out-group relations. Anthropologists are then well poised to investigate and combat societal issues such as bullying, which have deeply relational causes but long-term negative economic and psychological effects. Moreover, as the data on bullying in Denmark shows, qualitative methods can really make a difference when policy-makers want to successfully combat difficult societal issues at a local level.

However, since many of these initiatives are clearly based on anthropological knowledge, we need to be better at acknowledging our discipline’s theoretical contributions. While anthropologists are gaining recognition for their ethnographic and qualitative methods, we are more than a methodology. We hold certain foundations, or what pioneering anthropologist of policy Cris Shore has termed an anthropological sensibility. Anthropological sensibility derives primarily from the fact that it takes a multiplicity of different perspectives and practices seriously. The dissonance between our own and others’ ways of thinking creates uncertainty, but it is in this oscillation of knowledge and perspectives that the insights arise that become anthropological knowledge. As Shore and Trnka write, context is everything in anthropology (2013:15).

And such a focus on relational context has helped to almost completely eliminate bullying in Denmark.

Leave A Comment