The Netflix drama Adolescence reflects a dangerous online reality

Many people have been introduced to the language of the manosphere through Netflix’s new show Adolescence, where Detective Inspector Luke Bascombe’s son, Adam, explains the meaning behind certain emojis and slang used by misogynistic online communities.

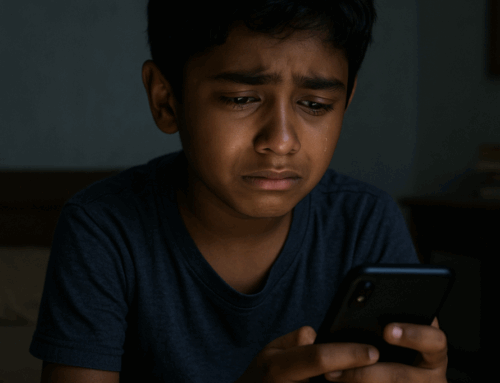

But what started as a TV subplot reflects a real and growing online phenomenon influencing the values and attitudes of boys and young men worldwide.

The term manosphere first gained traction around 2009–2011 in blogs criticising feminism and promoting so-called “men’s rights.” It was popularised by bloggers like The Spearhead and Return of Kings, and is now widely used by the media, academics, and online safety organisations — though it remains controversial because it covers a wide spectrum, from mainstream men’s rights activists (MRAs) to extreme misogynist and violent groups such as incels.

Scholars like Dr. Debbie Ging (Dublin City University) and Dr. Kaitlynn Mendes have written extensively about the manosphere’s discourses and impacts. Ging’s article “Alphas, Betas, and Incels” is considered a key resource, while Mendes co-authored Digital Feminist Activism: Girls and Women Fight Back Against Rape Culture.

Language as a gateway to radical beliefs

In Adolescence, when Luke visits his son’s school, he learns that students have been exposed to manosphere communities. Adam explains the emojis Katie left on Jamie’s Instagram profile, including the red pill emoji.

The red pill is one of the manosphere’s most powerful symbols, taken directly from the 1999 film The Matrix. In the movie, taking the red pill allows a person to “wake up” to reality. Manosphere communities have adopted it to symbolise what they see as an awakening to the supposed truth that society discriminates against men, not women.

Katie uses this emoji in the show to label Jamie an incel — a term for a misogynistic man who is involuntarily celibate.

Adolescence dramatises how slang and symbols that start as pop culture references can become gateways to more extreme misogynistic ideologies. Language becomes the first step in drawing individuals deeper into these belief systems.

How influencers profit from male insecurity

Manosphere influencers such as Andrew Tate prey on boys and men who feel isolated, insecure, and uncertain of their place in society. Tate glamorises a gangster lifestyle, posing with cigars and money, marketing himself as the ultimate “Top G” — his term for a “Top Gangster” man who is dominant, wealthy, and sexually successful.

A 2023 Hope Not Hate report found that 45% of young UK men aged 16–24 held views aligning with Tate’s narratives. A YouGov poll reported that 20% of British teenage boys had a favourable opinion of Tate despite his criminal convictions. Research by the Centre for Countering Digital Hate documented the reach of manosphere influencers on platforms like TikTok and YouTube.

These influencers offer supposed solutions to men’s struggles: wealth, power, traditional gender roles, and the dismissal of men’s emotions. Tate and others monetise this ideology by selling online courses (like The Real World), unregulated supplements (such as his Fireblood pills), and self-help books.

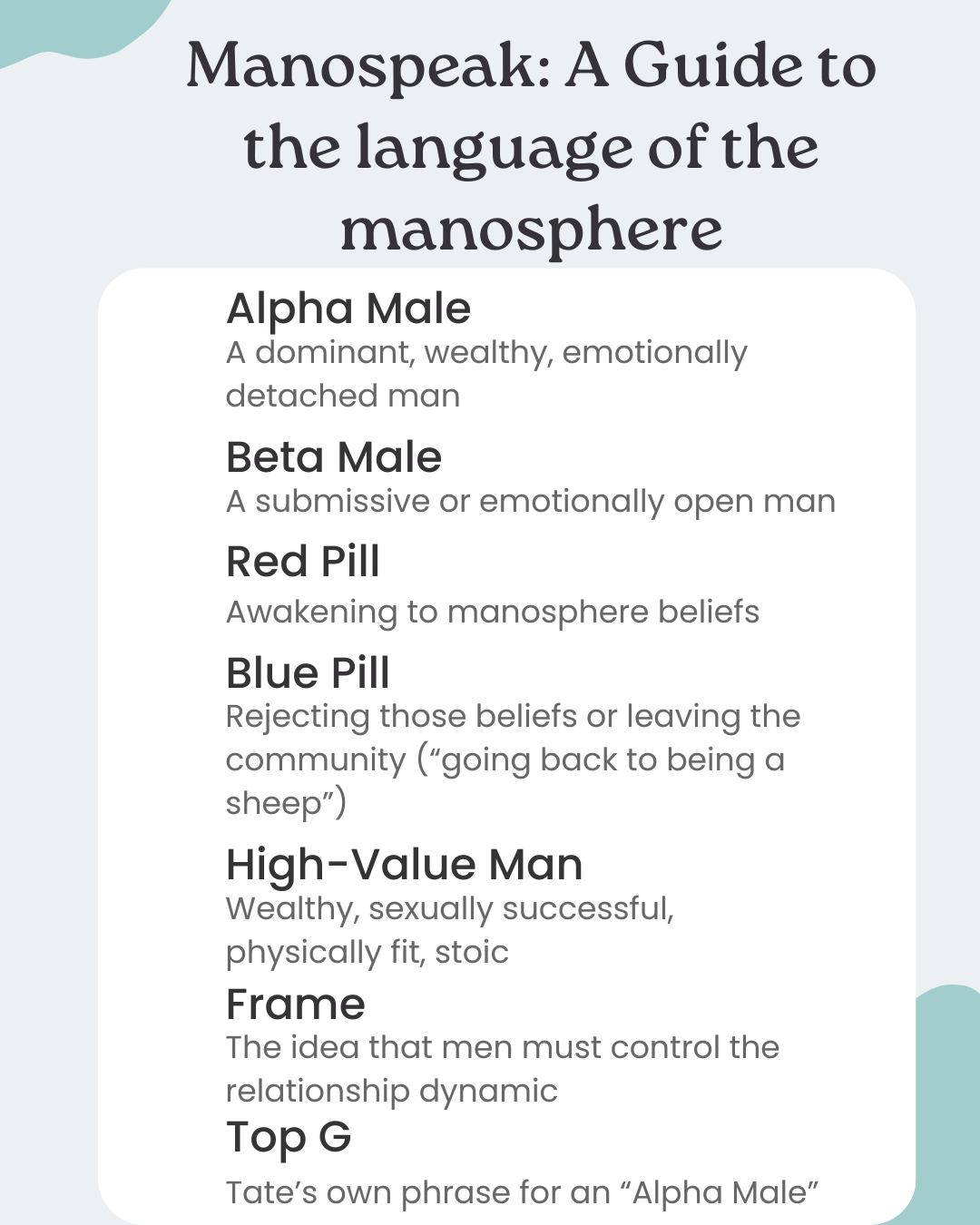

The language of the manosphere — and what it reveals

Manosphere language works both as a recruitment tool and a way to deepen radical beliefs.

Manosphere influencers, like Rollo Tomassi (author of The Rational Male) and Myron Gaines of the Fresh & Fit podcast, use and popularise these terms, once found only in obscure online forums like 4chan. Our contributor Baris Isik shares his own story of being radicalised by these communities in “Three Clicks Away from Radicalisation”.

The real-world consequences — and the possibility of change

Sometimes, even influencers are forced to confront the harm they have caused. In a now-famous video, influencer Sneko was shocked when a young fan declared, “We hate women.” When Sneko corrected him, the boy added, “But we hate transgender people.” Sneko, horrified, replied, “No, no, we love everybody,” before looking into the camera and saying, “What have I done?”

This moment captures the real-world effects of manosphere rhetoric. It promotes misogyny and contributes to the male loneliness epidemic by discouraging emotional vulnerability and empathy.

Yet, people can leave. Former manosphere figures like Kevin Ray Wilder and Caleb Cain have publicly documented their deradicalisation journeys. Cain, who was pulled into alt-right and manosphere content by YouTube algorithms, credits the YouTuber ContraPoints (Natalie Wynn) for helping him rethink his views. His story was featured in The New York Times article “The Making of a YouTube Radical”.

Support groups such as Life After Hate, ExitUSA, and the Centre for Analysis of the Radical Right (CARR) now help others seeking to break free from extremist online communities.

Author: Chloe Clarke, volunteer writer, Power of Zero.

Leave A Comment